Welcome Back

Andrei Platonov: Russia's greatest 20th-century prose stylist?

Stalin called him scum. Sholokhov, Gorky, Pasternak, and Bulgakov all thought he was the bee's knees. But when Andrei Platonov died in poverty, misery and obscurity in 1951, no one would have predicted that within half a century he would be a contender for the title as Russia's greatest 20th-century prose stylist. Indeed, his English translator Robert Chandler thinks Platonov's novel The Foundation Pit is so astonishingly good he translated it twice. Set against a backdrop of industrialisation and collectivisation, The Foundation Pit is fantastical yet realistic, funny yet tragic, profoundly moving and yet disturbing. Daniel Kalder caught up with Chandler to talk about why more people should be reading Platonov.As most of you who are on our e-mail list already know, IndieLitNow is back for good. We’ve switched our address, due to a copyright discrepancy that we won’t go into, except to say that it involves an exclamation point! That said, we’ve reposted most of our backlog, and are starting fresh here and now. Printed issues of IndieLitNow will be available, same as always, during the months of January, April, and August.

More importantly, IndieLitNow correspondent Micah Loosen has compiled this year’s list of Five Great Writers You’ve Never Heard Of. The idea this year is to alternate between writers of the past, and current authors. Coming in at number five this year is 20th century prose stylist Andrei Platonov.

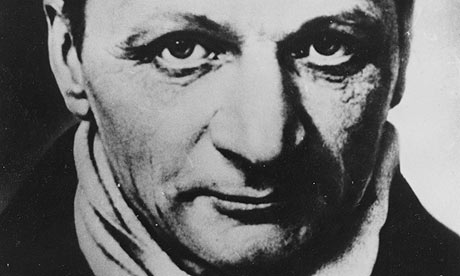

His writing 'works on many levels' ... The anti-Soviet author Andrei Platonov:

Why did you translate Platonov's Foundation Pit twice?

No other work of literature means so much to me. I translated it together with Geoffrey Smith in 1994 for the Harvill Press, and again in 2009, together with my wife Elizabeth and the American scholar Olga Meerson, for NYRB Classics. There were two reasons for retranslating it. First, the original text was never published in Platonov's lifetime, and the first posthumous publications – on which our Harvill translation was based – were severely bowdlerised. One crucial three-page passage, for example, is entirely missing.

Second, Platonov is hard to translate: in the early 1990s we were working in the dark. During the last 15 years, however, I have regularly attended Platonov seminars and conferences in Moscow and Petersburg. One indication of how deeply many Russian writers and critics admire him is the extent of their generosity to his translators; I now have a long list of people I can turn to for help. Above all, I have the good fortune to have my wife, who shares my love of Platonov, and the brilliant American scholar, Olga Meerson, as my closest collaborators. Olga was brought up in the Soviet Union; she has a fine ear, knows a great deal about Russian Orthodoxy, and has written an excellent book on Platonov. She has deepened my understanding of almost every sentence.

You've argued that Russians will eventually come to recognise Platonov as their greatest prose writer. Given that he's up against titans such as Gogol, Tolstoy and Chekhov this is quite a claim.

Well, it probably sounds less startling to Russians than it does to English and Americans. I've met a huge number of Russian writers and critics who look on Platonov as their greatest prose writer of the last century. In my personal judgment, it was confirmed for me during the last stages of my work on Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida, an anthology of short stories I compiled for Penguin Classics. I worked on this for several years, did most of the translations myself and revised them many times. I read through the proofs with enjoyment – I was still happy with the choices I had made – but there were only two writers whom I was still able to read with real wonder: Pushkin and Platonov. Even at this late stage I was still able to find new and surprising perceptions in Pushkin's The Queen of Spades and Platonov's The Return. This didn't happen with any other writers.

Readers who encounter Platonov for the first time are often struck by his surreality: in the Foundation Pit, for example, a bear staggers through a village denouncing kulaks [supposedly wealthy peasants]. But you've said that almost everything he writes is drawn from reality.

Platonov's stories work on many levels. When I first read his account of the kulaks being sent off down the river on a raft, I thought of it simply as weird. Then I realised that it's one of many examples of Platonov's way of literally realising a metaphor or political cliché; the official directive is to "liquidate" the peasants – and this unfamiliar word is interpreted as meaning that they must be got rid of by means of water.

Many years later I found out that this scene is also entirely realistic. The Siberian Viktor Astafiev wrote in his memoir: "In spring 1932 all the dispossessed kulaks were collected together, placed on rafts and floated off to Krasnoyarsk, and from there to Igarka. When they started loading the rafts, the whole village gathered together. Everyone wept; it was their own kith and kin who were leaving. One person was carrying mittens, another a bread roll, another a lump of sugar." Any educated Russian reading these lines today would at once imagine that they were written by Platonov.

As for the bear, he's drawn from many sources. He is the generally helpful but somewhat dangerous bear of Russian folk tales; he is a representative of the proletariat – strong but inarticulate. As a hammer in a forge, he is linked both to Stalin, whose name means "man of steel" and to Molotov, whose name means "hammerer". He is the tame bear often employed by a village sorcerer. Platonov's bear "denounces" kulaks by stopping outside a hut and roaring; in the late 1920s an ethnographer working in the province of Kaluga recorded the belief that "a clean home, outside which a bear stops of his own accord, not going in but refusing to budge – that home is an unhappy home". And one of Platonov's brothers has written that there really was a tame bear who worked in a local blacksmith's.

Platonov started off as a committed communist, but was appalled by collectivisation and the excesses of Stalinism. Uniquely – unlike others who adopted an oppositional stance, or wrote critiques for the desk drawer – he tried to negotiate a space within Soviet culture in which he could write honestly about what was going on. Is it fair to say that he failed?

I don't think so. Some of the stories he managed to publish – The River Potudan, The Third Son and The Return – are as great, in their more compact and classical way, as the novels he was unable to publish. The Return was viciously criticised, but it was published in a journal with a huge circulation and may well have been read by hundreds of thousands of people. And there is no knowing how important Platonov's example was to younger writers. Vasily Grossman, for example, was a close friend. They met frequently during Platonov's last years and read their work out loud to each other. Grossman gave the main speech at Platonov's funeral. His last stories are very Platonov-like. And Platonov's very last work – the moving, witty versions of Russian folk tales he composed after the war – was included, without acknowledgment, in millions of school textbooks. Platonov was not widely known, but he was widely read. Here again he is in a similar position to Grossman, whose words are carved in granite, in huge letters, on the Stalingrad war memorial, without acknowledgment of his authorship.

Platonov's language is often extremely intimate yet also strange: alienated and alienating. Is he exceptionally difficult to translate? And does he sound more "normal" in the original than in translation?

He is certainly difficult to translate. On the other hand, I've sometimes been surprised by how much of him evidently survives even in a poor translation. I've met people who have been deeply moved after first encountering him in a very poor translation indeed. As for your second question, you need to ask someone who is entirely bilingual and not involved in the work. All I can say myself is that all languages have norms that can be infringed, and that we do our best to infringe English norms just as Platonov infringes Russian norms. It is for you and other readers to judge how much we have succeeded!

Sometimes I think you have a secret plan to steer readers away from familiar authors such as Chekhov towards more angular, difficult work such as Platonov, thus reshaping perceptions of 20th-century Russian literature.

Well, I'd put it at least a little differently! I love Chekhov's stories as much as anyone, and would especially love to translate The Steppe and A Boring Story. But then Chekhov isn't so very easy or smooth either, though many of his complexities and contradictions are smoothed over in translation. What's certainly true is that I think we have a distorted view of Soviet literature. For many decades it was impossible for a Soviet writer to achieve fame in the west except through a major international scandal. This is what happened with both Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn. Both are important writers, but they are not greater writers than Grossman, Platonov and Shalamov.

Things are changing, however. Grossman is far better known in the west now than he was 10 years ago. Platonov is at least beginning to be noticed – Penelope Fitzgerald and John Berger are two of the English writers who have been quickest to realise his genius. And there is a chance that the Yale University Press will soon be commissioning a complete translation of Shalamov's Kolyma Tales. One more point: we have found it easier in the west to learn to appreciate the 20th-century writers who wrote from outside the Soviet experience. Bulgakov reached adulthood long before the revolution. He was never taken in by it; he looks down on everything Soviet. Grossman, Platonov and Shalamov, however, belong to a generation 10 to 20 years younger. All of them, at least for a while and to some degree, shared the hopes of the revolution. They write from inside the Soviet experience. This perhaps gives them a greater depth and complexity; their work contains no ready-made answers.

No comments:

Post a Comment